Food security: solely a water problem?

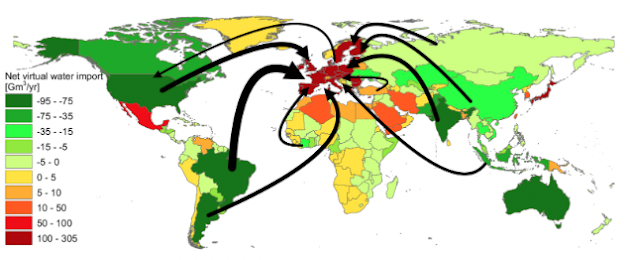

For my final post, I thought it would provide useful context to consider some of the other factors contributing to food-related issues in Africa to avoid framing it as a one-dimensional problem. This means that many of the solutions I have proposed throughout this blog will not alleviate food issues in Africa in isolation. The factors discussed in this post also play a significant role. The previous post looked at the potential of virtual water to alleviate food shortages through importing water-intensive agricultural commodities. However, this approach appears far-fetched considering affordability issues of local produce in most African countries. Food affordability is the main driver of food choice and a barrier to consumption of nutritious foods. For example, only 24% of children in Eastern and Southern Africa receive a minimum balanced diet leading to widespread micronutrient deficiencies ( UNCF, 2019 ). Interestingly, evidence suggests that issues of food affordability in Afr...