So far, this blog has focused on traditional methods of ensuring water and food security like irrigation schemes and groundwater extraction. However, there exist more abstract solutions, including virtual water, that may offer equally promising avenues.

Put simply, virtual water measures the water that is 'lost' in the production of any commodity (Allan, 1997). I isolate agricultural commodities due to their water-intensive nature - it requires 1000 cubic metres of water to produce a ton of grain (Allan, 2003). Therefore, virtual water can be harnessed as another method of achieving water and food security. This view argues that the bluewater used in irrigation is an inefficient use of resources when these crops, at least highly water-intensive ones, can be imported from elsewhere (Zeitoun et al., 2010).

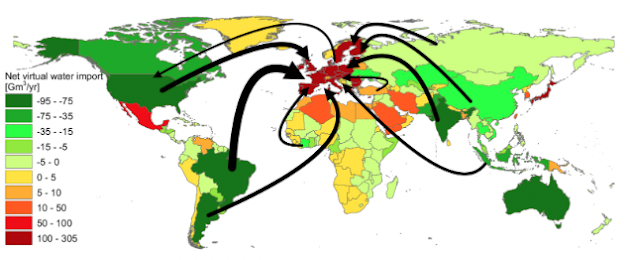

Whilst we've analysed issues of water and food scarcity on a strictly continental scale, this is a gross simplification of reality. Virtual water allows us to globalise these issues.

The map shows that whilst drier areas tend to be net importers of water, Africa doesn't follow this trend. I now weigh up the case for the continent to leverage the virtual water trade.

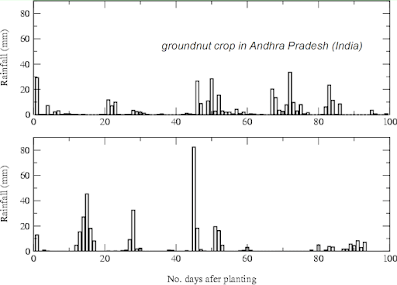

Using the example of Libya, the economic, social and environmental benefits of harnessing virtual water are clear. Rainfall is highly variable and most concentrated in the winter with 93% of the land surface receiving less than 100mm annually (

World Bank, 2021). Unreliable rainfall initiates reliance on irrigation schemes and over-extraction of groundwater for agriculture. This necessitated the £14 billion Libya Great Manmade River project to extract Saharan groundwater through a network of pipes although it is only expected to last 20 years (

Kuwairi, 2006). Importing these water-intensive commodities using the virtual water trade appears an ideal solution for Libya.

However, my research into virtual water helped me understand why it hasn't translated into an effective policy criterion. Whilst providing food security, importing agricultural commodities can actually hamper water security (

Hirwa et al., 2022). It reduces the urgency to reform existing water-use practices, like those inherited from colonialism discussed in the previous post, towards an equal and sustainable future. Furthermore, the opportunity cost of not being agriculturally self-sufficient must be considered. Lacking water quality and sophisticated infrastructure raises questions over how else water resources can be used to create economic value (

Wichelns, 2009). With most African countries already having to import manufactures and services, using virtual water for agriculture raises concerns over local livelihoods and balance of payments.

To conclude, virtual water is more a useful alternative perspective on issues of water and food than an effective policy tool. Currently, Africa is unable to reap the benefits of the virtual water trade due to unintended consequences on economic indicators and farmers' livelihoods. This is also subject to political and economic barriers to trade that hamper implementation.

For me, this post is the highlight of your blog. Virtual water is a really interesting topic that I hadn't thought about in writing my own blog. Even though I studied it during the Human Ecology module in first year, I didn't see the link to issues of water and food in Africa. You have provided some really useful case studies that I want to look into further for my own blog. I think it would help if you went into more detail on how international trade policies hamper the implementation of virtual water policies as you have touched on it very briefly at the end.

ReplyDeleteHi Mihir, I'm glad you found this post useful for your own writing. As far as expanding international trade policies goes, this will be the focus of my next post! I encourage you to have a read and hope you find it useful.

Delete