Water Grabbing

I concluded my previous post by emphasising the importance of tackling power and control abuses by governments and institutions over communities. This is the first of two posts looking into specific instances of this. Water grabs are the extensive acquisition of land by companies or governments where water is implicitly or explicitly given away with the land.

Foreign investors have acquired huge quantities of fertile agricultural land in African countries like Zambia (Chu, 2012). There is conflict over the viability of large-scale investment in Zambia where the aggregate of land deals is equivalent to 12.92% of total arable land, increasing pressures on farmland (Keane, 2011). The common narrative behind these deals is governments from 'finance-rich, resource-poor' nations are turning to 'finance-poor, resource-rich' countries to secure their own future food and energy requirements (Borras & Franco, 2010: 508). However, these land grabs become water grabs as investors demand a reliable water supply, seeing governments signing away water rights in a continent where access for domestic purposes is limited. For example, in the Nasanga Farm Block - a 150,000 ha venture - the Zambian government has given Hungary-based BonaFarm Group unlimited water alongside advice like growing less water-intensive crops between January and May. The Oakland Institute has voiced its concerns over these soft regulations and the lack of transparency in the allocation process (Bond-Graham, 2011).

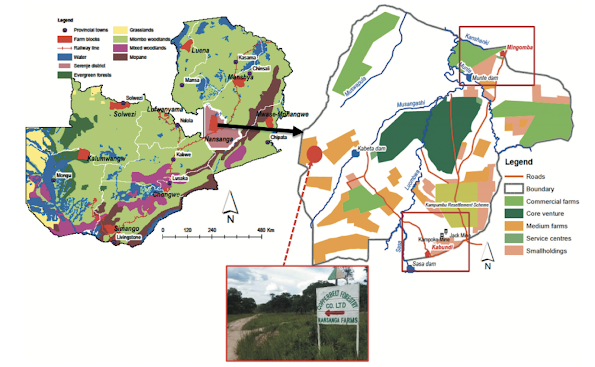

CLICK TO ENLARGE: Nasanga Farm Block (Chilombo, 2021)

This allocation to agribusiness and intensive development of the Nasanga area has catastrophic implications for others that rely on these resources. China Geo Engineering Company were appointed to build over 30km over power lines, 155km of roads, and four dams with more expected (Lusaka Times, 2010). The environmental impact assessment (EIA) report (MACO, 2006) outlined the adverse consequences of such infrastructure projects including declining fishing yields and water supply, although without recourse for preventative measures. Reports claim 9,000 people would be displaced because of the farm block with lacklustre relocation efforts further threatening local livelihoods (Chanda, 2011).

Whilst there is scope for critiquing water grabbing institutions, this does not exempt governments from a portion of the blame for instilling the conditions to allow it. The Zambian government enacted the Fifth National Development Plan (FNDP) between 2005 and 2010 where agricultural growth was targeted to shift the economy away from traditional mining and construction. Underpinning this is the commitment to increased irrigation by investing in appropriate technologies. With such generous policies, it was only a matter of time before investors pounced. Interestingly, the FNDP period closely correlates to the starting dates of land and water grabs in Zambia (Chu, 2012). It is apparent that social and environmental impacts on local watersheds have become of secondary importance to economic development.

Frameworks for governing the global rush for land and water are complicated. I paraphrase by outlining a three-pronged approach that protects local communities, the environment, and valuable resources:

1. Total respect for the human right to food and water enforced by an export cap, or ban

2. Locals to be included in planning and negotiation process of deals

3. Protection and sustainable use of natural resources. Promising investors unlimited water is unrealistic in water-scarce climates.

I really liked this post, it is something I haven't thought about in my own writing. It is true that water scarcity is so easy to blame for inadequate food production while there are so many factors and actors at play. As you described in your introductory post, there are undeniable physical constraints, more so in some areas than others, and there are issues with national governments, but importantly there are also many outsiders with financial resources unconcerned about the ramifications of their businesses for the country. In terms of improvement for this entry, the figure is too small and difficult to read, perhaps it would add more value to only keep the right-hand side part of it and larger?

ReplyDeleteHi Karolina,

DeleteGlad you found this post of interest and I hope you can incorporate these concepts into your own blog! Thank you for the feedback too, I will make the relevant changes and bear this in mind for future posts.