Introduction: The complex relationship between water and food

I’ve decided the best way to structure this first post is to discuss the reasons behind choosing my thematic area before providing some useful context. It presents an opportunity to build on my understanding of the complex relationship between water and food from my study of Human Ecology where the evolution of competing discourses within this space stood out to me. Naturally, this provides scope for nuanced critique to illustrate my own perspective through this blog.

I now outline some of these competing arguments. Traditionally, the literature widely accepted that acute food shortages were brought about by food-availability decline (FAD) meaning a fall in aggregate food production (Basu, 2010). This could result from fluctuations in physical variables, perhaps rainfall, or extreme geopolitical events. Regardless, this reduces the relationship between water and food to a linear one – water scarcity leads to a fall in aggregate food production which threatens food shortage.

This logic has since been rendered obsolete largely owing to the work of Amartya Sen. He disputed FAD theory by noting that famines often occur even when there is adequate food at the national or local level explained by the failure of ‘exchange entitlement’ (Sen, 1981). This changed the discourse of causal factors from supply-side to demand-side adding a geopolitical and socioeconomic dimension to the relationship between water and food.

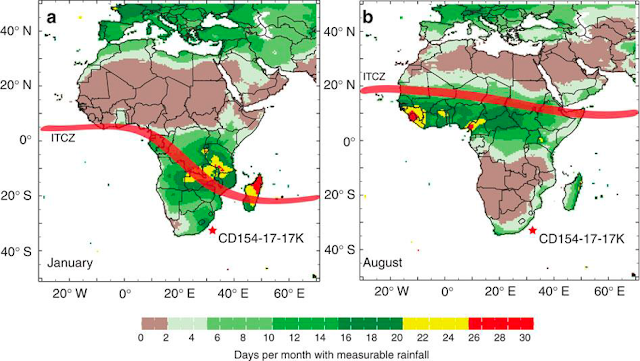

However, Africa's physical characteristics shouldn’t be ignored. I briefly outline these for context. Whilst annual precipitation can reach 2000mm in areas, it is highly uneven with little rainfall outside the equatorial belt. Seasonal variability in precipitation corresponds with the position of the ITCZ. As shown below, the equatorial belt has its rainy season in July compared to January South of the tropics.

Ziegler et al. (2013) Nature Comm. 4, 1905.

Moreover, the geological and hydrogeological setting for groundwater storage is important. Precambrian crystalline basement rocks occupy 34% of the land surface of Africa which comprise little primary permeability or porosity to hold water (Gaye & Tindimugaya, 2019). That said, ancient Saharan groundwater reservoirs make it the most water-rich area on the continent. Immediately, one can anticipate this blog will mainly be addressing issues of water management and distribution.

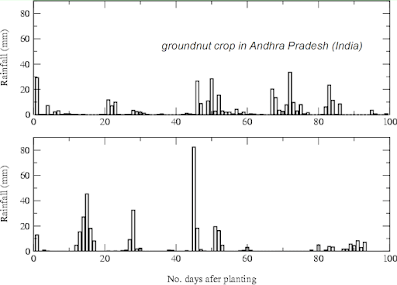

Wright (1992) Geol Soc Lond. 66, 1-27.

The Ethiopian famine of 1984-1985 clearly demonstrates the interplay of physical and human causal factors. It is widely accepted that drought placed an initial strain on food supply driving up prices (De Waal, 1991). However, it was the withdrawal of state support to agriculture since the 1980s and political decisions around the provision of aid that left the agricultural system vulnerable to full-blown famine (Devereux, 2009). Evidently, FAD decline alone is unlikely to induce famine in the absence of other factors. I encourage you to watch this video for further examples of this:

This blog focuses on said factors governing Africa’s water as achieving sustainable management of these resources directly impacts food security and development (Braune & Xu, 2008). I hope to develop progressively more sophisticated arguments around this theme throughout my study of Water and Development in Africa.

A really interesting start to your blog! I like how you have contextualised some of the issues on the African continent and set out topics you want to tackle in future posts. I look forward to following your blog and hopefully building some of your ideas into my own writing. Good luck!

ReplyDelete