How big a risk does climate change pose to Africa's food security?

Much of the Western literature is highly pessimistic of Africa's ability to ensure reliable food supply with climate change. Following lectures from weeks 4 and 5, I summarise competing arguments and aim to take a more constructive approach.

Key to this post is understanding the projected impact of climate change on Africa's hydrological systems. As established in the previous post, hydrological disruption has significant (but not total) consequences for food supply. The principal impact of climate change in tropical areas is increased rainfall variability with more severe precipitation events and fewer moderate ones (Fischer & Knutti, 2019).

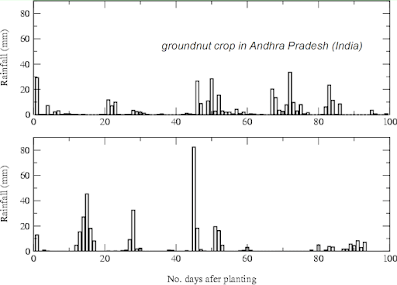

The effects of this, which I now summarise, are widespread. Episodic precipitation induces more variable soil moisture impairing crop yields. The graphs below compare a year of steady rainfall (1975) with one of episodic rainfall (1981) in Andhra Pradesh, India. Despite total rainfall being unchanged, crop yields were 34% lower in 1981. With climate change expected to be more intense in tropical climates, this may necessarily point to expansion of land under irrigation as an adaptive strategy.

Moreover, highly variable rainfall produces even more variable river discharge and longer, more frequent droughts. Further, groundwater storage is compromised due to intensification of precipitation and evapotranspiration with increased likelihood of aquifers running dry between heavy rainfall events (Wu et al., 2020). This is exacerbated by rapid urbanisation at a rate seven times faster than the developing world leading to infrastructures becoming overwhelmed (Cobbinah et al., 2015).

This is a damning proposition. However, Washington et al. (2006) maintains that adaptation to existing climate variability will go a long way to adapting to climate change. This means we must assess different approaches to ensure that Africa can position itself optimally as climate change intensifies.

Two distinct approaches to water management have been deployed in Africa, the first being top-down engineering solutions. These have generally failed to accurately identify and alleviate local issues, but persist because of institutional inertia. For example, critics of the Akosombo Dam consider it an economic project rather than one tailored to local needs. Whilst promises to support irrigation were made to approve construction, these were soon dropped from plans (Miescher, 2014). Today, almost all its energy serves aluminium smelting. This video essay illustrates the conflicts around Akosombo's construction:

Since, sustainable freshwater management projects based on full public participation have emerged embodied by UNCED's Integrated River Basin Management. This contributed to successful management of the Pongolapoort reservoir on South Africa's Phongolo. Whilst initial flood releases from the reservoir were unsuccessful and poorly timed, this was mitigated following consultation with farmers, fisher-folk and other stakeholders thereby involving floodplain communities in floodplain management (Bruwer et al., 1996).

Climate change does threaten Africa's water and food security. With rapid urbanisation and the proposed expansion of irrigated land, increases in freshwater demand are projected. This can be mitigated through multi-sectoral, inclusive management of water resources based on community needs. However, conflicts of interest at the institutional level may impede this.

Your posts demonstrates reasonable grasp of water and food issues in Africa, and the two posts build on each other showing engagement with relevant literarues. However, some of the points you raised about water and food intersection could use some clarification. For instance, how do you reconcile the experience of rainfall distributions in Andhra Pradesh, India between 1975 and 1981 with the experiences from the African continent? And what are the specific implication of Akosombo dam for local food production?

ReplyDeleteThanks for your feedback, Clement. You have raised some good points and I have made some changes to rectify this. I used Andhra Pradesh, India as there was data readily available and it provided an interesting scenario. I have now related this to experiences on the African continent by arguing that climate change is set to be even more severe in tropical climates so we will likely see an even more extreme decline in crop yields. Also, I have developed my argument of the Akosombo dam to reveal how economic and political self-interests behind its construction diminish its effectiveness in boosting food production. I've also included a video for further detail on this.

Delete